This week, 2 stories on the history and continued life (and problems) of paper checks in modern banking. Also, we look at how data and technology are reshaping one corner of financial services: property insurance.

1. The long shadow of checks

Patrick McKenzie presents a “how we got here” trip through the history of checks. He walks through the ins and outs of why checking accounts are fundamentally credit products, when NSF means Now’s Somebody’s Felon, the role of the ChexSystems, and the how Check 21 ushered in mobile banking.

Check 21 also paved the way for remote check deposit as a product. Your bank’s mobile app very likely allows you to take a picture of a check to deposit it.

It was 2003, a surprising portion of small banks still had immaterial usage of the Internet in their operations. Most of them did not own their technical destiny but rather are at the mercy of various vendors.

Check 21 said “OK, the rest of the industry hears that explanation, and we actually sympathize a bit, but we won’t let you block an industry-wide improvement. We will instead give you a carve-out: you and you alone will still get the daily delivery of a lot of paper. It will just be new paper, with substitute checks printed on it, from a printer we have arranged to locate very close to your check processing address. We will legally compel you to treat that paper exactly like the special magically formatted check paper.”

2. Americans love paper checks; thieves love them more

In the same vein, Tara Siegel Bernard of the NYT looks at the increasing rate of check fraud, how banks deal with it, and the effects on customers.

A recent surge in mail theft caused the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network — an arm of the Treasury Department known as FinCEN that is charged with safeguarding the financial system — to sound alarm bells this year. Thieves have attacked mail carriers, or stolen and sold carriers’ arrow keys, which unlock mailboxes within a certain area.

Banks and credit unions are expected to file nearly 540,000 suspicious activity reports tied to check fraud this year, a record, according to a Thomson Reuters analysis of data from FinCEN. That’s about 7 percent higher than 2022, but more than double the levels in 2021, when fewer than a quarter-million such reports were filed.

Regions Financial in Birmingham, Ala., has filed its fair share: Last month, it admitted to Wall Street analysts that it had become entangled in a check scheme that went undetected for long enough that its fraud costs — $136 million so far in 2023 — would double this year.

“We opened the door too wide, bad people came rushing in, and we didn’t close the door timely enough,” (Regions CFO) David Turner said. “What happens is they get on the dark web and they start talking to each other, and they just overwhelm the system.”

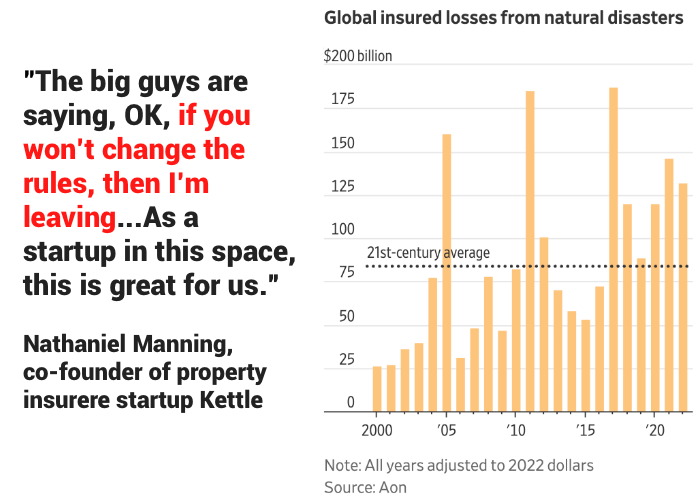

3. Climate change and parametric insurance

Christopher Mims at the WSJ looks at the evolving property insurance market as more long-standing incumbents are leaving the market. This move has opened the door to new data-driven companies and potentially a disruption of the entire industry.

Owners of homes and businesses have watched with alarm as major insurance companies have stopped offering coverage in California, Florida, and other parts of the country prone to natural disasters. But this shift has also created an opportunity for new types of insurers.

The secret sauce of these startups is technology. They are using better data science and incorporating artificial intelligence. Some, like FloodFlash, use on-the-ground sensors that enable an automatic payout when a catastrophe occurs.

Another way to insure properties in a world where insurance companies can no longer afford to cover the full replacement cost of a building is parametric insurance. The customer and the insurance company agree on a flat payout if a specific event takes place.

And that it for this Friday. It’s probably not good news for you if your lawyer describes you as “the worst witness I’ve ever seen”. Click below to let us know how we did: