Bloomberg’s Matt Levine offers this simple analogy of how community banking works:

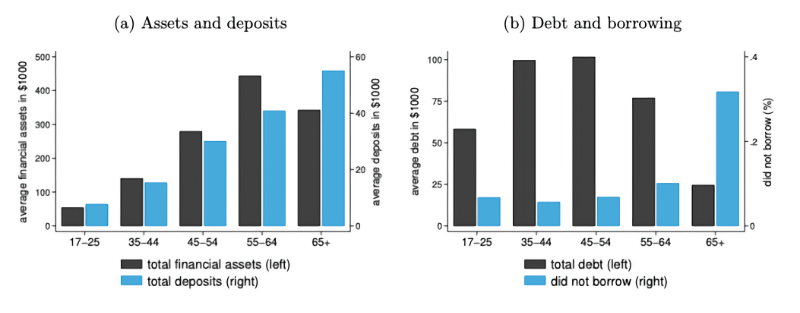

- Banks exist to take the old people’s money and lend it to the young people, making everyone better off: The young people get to consume more now; the old people get to keep their money somewhere safe and live off the interest.

But what happens if there’s an imbalance? In this analogy, too many young people, and you’ve got a plethora of lending opportunities but not enough deposits to match. Your credit decisions tend to be better, but you must expand to find a deposit base you can hopefully develop into a franchise.

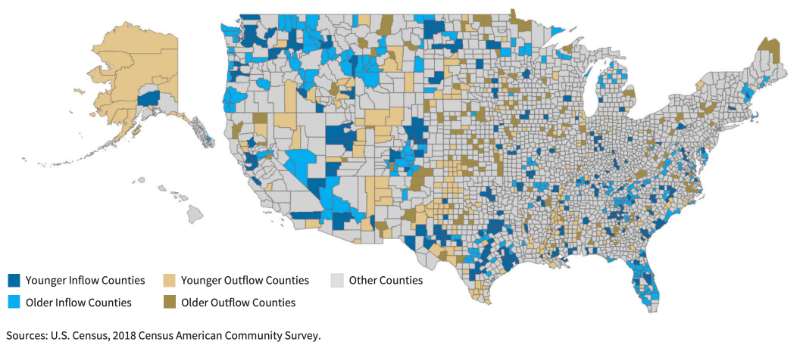

The opposite of that is what many community FIs are facing today. In many counties, the net migration of people is pushing this imbalance even higher. Here, you face plenty of capital, maybe a healthy franchise of sticky deposits, but not enough younger borrowers (and, by extension, commercial opportunities). But does that lead to poorer credit decisions?

In that vein, The Swiss Finance Institute released a research paper on Population Aging and Bank Risk-Taking.

What are the implications of an aging population for financial stability? To examine this question, we exploit geographic variation in aging across U.S. counties. We establish that banks with higher exposure to aging counties increase loan-to-income ratios. Laxer lending standards lead to higher nonperforming loans during downturns, suggesting higher credit risk. Inspecting the mechanism shows that aging drives risk-taking through two contemporaneous channels: deposit inflows due to seniors’ propensity to save in deposits; and depressed local investment opportunities due to seniors’ lower credit demand. Banks thus look for riskier clients, especially in counties where they operate no branches.

Silicon Valley Bank could be seen as suffering from a similar situation. The bulk of their startup clients were like older depositors, with a lot of cash (financed through venture capital investors) and not really borrowing. SVB ran into trouble by being too long in duration of Treasuries.

However, the problem arises when institutions begin offering loans outside their home turf.

Previous work has further shown that a greater borrower distance to the nearest branch requires banks to rely more on hard information. A greater distance can hence result in less efficient screening and monitoring of borrowers, leading to the build- up of risks. These considerations suggest that an increase in LTI ratios in counties where banks have no physical presence could lead to greater increases in credit risk.

Looking back at the ratios from over 1,800 institutions over the past 25 years, the paper’s authors found a direct correlation between an aging market and risk measures like loan to income.

Banks more exposed to aging counties increase their loan-to-income ratios by more and experience a sharper rise in nonperforming loans during the Great Recession. Inspecting the mechanism, we find that an aging-induced inflow of deposits, together with a decline in the local demand for credit, explains the link between population aging and bank risk-taking.

The question for institution leaders -> are your customers following or bucking this trend? If no, do you have an early warning system in your customer intelligence process? If yes, do you have plans to mitigate it?